She had painted throughout her life, to some degree, but she hadn’t shown anyone.

Anne Jenkins, born and raised in South Africa, had married a man who, as the son of a diplomat, was accustomed to travel. Together, they had lived in Germany, Greece, Turkey, England, Spain and France. For 5 years they had lived on a sailboat. Through all of their adventures, Jenkins would find time to paint with watercolor.

Now they had made the United States their home, and, in 2003, were drawn to New Orleans. She met many artists at the monthly, juried art markets in nearby parks.

Jenkins had started dabbling in acrylics, enjoying the thickness of the paint, when a colleague on the market told her that her style would suit a palette knife. She went to Wal-Mart and bought three plastic palette knives. She didn’t know what to do with them.

“And I got home, put a canvas out, put some paint out because I used thick paint anyway,” she says. “And I started painting with a palette knife, and it was like a light bulb went off. It just was, ‘Whoa, this is what I’m supposed to do.’ And I’ve painted with a knife ever since.”

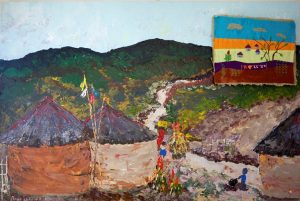

Hers is a quick-moving impressionistic style, which is to say that she moves her palette knife as freely as she shifts her life’s setting.

“And so I’ve traveled all my life without any regard for how I’m going to pay for my old age,” Jenkins says, “which means I’m going to have to work and paint for the rest of my life, which is fine!”

In the last few years, though, she increasingly has sought “to do more than just paint pretty pictures.” The Milford resident has been working with a group of seven to nine women from rural Kwa-Zulu Natal, her home province in South Africa. The women are members of a support group for those living with HIV and AIDS, focusing on the children.

“I grew up in that area, and the Zulus looked out for me a lot when I was a child,” Jenkins says. “And I just thought, this was a chance I could do something to give back.”

She has collaborated with her sister, a quilter and teacher, and a few others in providing sewing lessons for the women to help fund their own efforts. The women have created small scenes on (and of) fabric and sent them to Jenkins’ Milford gallery. There, she attaches them to tote bags. Through her gallery and via Bag of Hope, Jenkins since December 2008 has sent the members of the support group about $5,000 of proceeds.

Her most recent collaboration with the women is called “The Vukuzakhe Project,” which in Zulu means “stand up and do it for yourself.” It comprises a series of seven 36-by-24-inch wood panels, each onto which she attaches plexiglass dowels to support a smaller fabric landscape sewn by one of the women. (This, Jenkins says, protects the fabric and makes it appear to float atop the larger painting.) With each piece, Jenkins has painted a larger scene that provides a fluid context for the fabric landscape.

She is selling each for $3,500, and the Zulu collaborators get half, akin to a year’s salary.

The colors are bright and bold, something different than the blues and whites that dominated the “Canvassing Delaware” series with which in 2011 she opened her gallery.

“Delaware,” she says, “I call it the wee state with the big sky.”

The topography reminds her of Holland and England, she says, where she once lived in another place by the name of Kent.

Masters

Established

Emerging

Related Topics: arts fellowship, arts grants, dance, Delaware, delaware division of the arts, Department of State, Division of the Arts, emerging artist, fellowship, fiction, folk arts, literary arts, literature, media arts, music, performing arts, poetry, recipient, State of Delaware, visual arts