She first saw the three children at a yard sale she was hosting. They walked up her driveway and into the garage, and Beth Trepper, ever the photographer, saw something.

“These kids were so cool,” she says. “First of all, their eyes were amazing. And they had these bubbly personalities, and they were very outgoing. And then their dad walked up, and he was really fun. I was so captivated by these children.”

“Do you think that I could photograph your kids?” she asked the man.

“Well,” he said, “you’ll have to ask my wife.”

He told Trepper of the spa where his wife worked. Trepper walked into her workplace, unannounced, and introduced herself.

“Hi, I’m Beth,” she said. “I’d like to shoot your children.”

“You know,” the woman replied, not missing a beat, “there are days I feel the same way.”

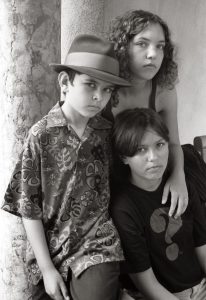

She granted Trepper permission to photograph her children, and the resulting images made it worth her while — in one, titled “Garage Sale Kids,” the three siblings pose closely together, an arm of Lynsey, the eldest, draped over the shoulder of her sister Camryn. The youngest, Cole, wears a fedora and a Hawaiian print shirt. Their gaze is magnetic.

Trepper, of Wilmington, submitted the photo in applying for a Division fellowship as part of a series titled “People You Won’t Recognize.” It’s a nod to her use of subjects who are “everyday people we all pass on the street, as opposed to models.”

She has two or three digital cameras, an infrared camera and many old film cameras. Trepper still uses a flip phone, and she learned to text within the past few months. But she doesn’t bemoan technological advances in her craft. She’s not stuck in a rut.

“I am old-school, but I don’t want to come across as sounding like a curmudgeon,” she says. “I just know that for me, it’s way, way, way more important for me to be in the moment of being an artist than to worry about the tools and the gadgets.

“I’m far more concerned if I can stir the soul of even one person through my art. My success isn’t measured in money as much as in this world creating beauty and keeping beauty alive for all of us.”

Trepper has been a photographer for more than 40 years. She began as a painter and illustrator working toward a fine arts degree, but fate stepped in when she picked up a camera for a class at the University of Delaware.

“It was love at first sight,” Trepper says, “and I never looked back.”

She’s always been a writer, too, so she combined her pursuits and majored in photojournalism with a minor in fine arts from Northern Arizona University. She started writing about music in college. When she finished school, she at one point moved to Tucson and started writing for a local music magazine, interviewing big-name artists who would call in from all over the world. Her roommate took her out to a bar one night, and reggae music was the focus.

“And I had not heard much reggae, even coming from Wilmington, Del., where Bob Marley used to live,” Trepper says. “Didn’t know that much about it, and fell instantly in love with it. For 12 or so years, I almost exclusively dealt with reggae music.”

She got a job with a record label in Washington, D.C. The label produced reggae from around the world, mostly from Jamaica, and it moved her from Arizona to D.C. She would shoot photographs to be used as record covers. She’d design sets for concerts. She’d put together press packets.

She toured the Southwest with Rastafarian musicians, serving as publicist, on a bus loaned to them by Bob Marley’s mother.

“My mother didn’t even tell my dad what I was doing,” Trepper says. “She said, ‘You know, your dad always wanted you to be a nurse. I don’t know that telling him that you’re hanging out with 27 Rastafarians on a bus in the desert outside of Yuma, Ariz., is what he envisioned for you.’ But it was a blast.”

She once went to the bottom of the Grand Canyon with a reggae band to write for a Los Angeles-based magazine. The group had been invited to perform by the tribal council of the Havasupai, a Native American tribe that has an affinity for reggae and its culture. They reached the performance space after hiking for several hours. The band’s equipment was delivered by helicopter in a net.

Trepper’s parents have been her priority for the past decade. She returned to Delaware to help care for her father, who since has passed away, and Trepper now is a full-time caregiver for her 93-year-old mother. (“She’s a blast,” Trepper says. “She’s a lot of fun. She’s my muse.”)

With her grant from the Division, Trepper hopes to replace her computer, which “sounds like a dying cow,” and perhaps dip into some of her craft’s technological innovations that until now haven’t figured in her work. She has a solo exhibition, “Half & Half,” throughout March at The Grand in Wilmington, will give a talk on fine art photography to the Delaware Photographic Society on April 3, and will display portraits at the Mezzanine Gallery in December.

Masters

Established

Emerging