He taught science and math for 44 years, so when Ray Magnani goes out to take pictures, he tends to look for and find more in what many people consider mundane.

Sometimes, he’ll take a drive in the country, or he’ll set out on a walk along a creek, and he’ll have a goal — to look at tree roots, or at leaves in the grass. “What kind of pictures,” he’ll ask himself, “can I make out of this little hike that I’m gonna take?”

Other times, as with many of the pictures in the series he submitted to earn a Division fellowship, his inspiration arrives unbidden.

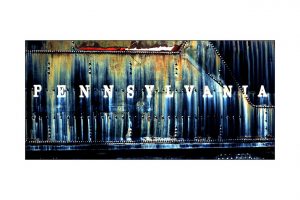

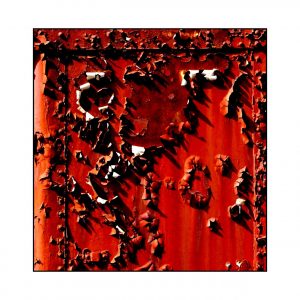

“I was out shopping,” he recalls, “and as I was walking up to the store, I thought, Well I’m gonna look behind the store and see what’s in the back. And there was this great Dumpster with this great rust and broken paint. I wasn’t planning to take that kind of picture that day, but I spent half an hour just walking around, crawling around with the Dumpters and the broken-down fence and all this garbage behind this store. And that started to get me thinking more and more in that direction.

“I start going out and saying, Let me find things that are decaying, that are rusting, that are falling apart, and what can I make out of this visually? Can I make a powerful, abstract image out of something that most people would just walk by without looking at twice?

“What are we seeing here? Why is that not just visually interesting but intellectually interesting?”

He got his first camera when he was about 12, and he hasn’t been without one since. In addition to math and science, he taught history and photography at the Newark Center for Creative Learning, a small private K-8 school from which he retired a year and half ago.

As a child, he always had a functioning darkroom. His father would print scores of Christmas card photos, and Ray would be running the chemicals. His father’s father made aerial photographs at an Oklahoma base during World War I using a camera that recorded images on 5-by-7 glass plates.

Through more than 50 years of making photographs, Magnani claims no one style. Sometimes he plans ahead — a multiple-exposure composition of an object from slightly different perspectives, for instance — and sometimes he’s struck by the way a feeling he has when he notices the light of a landscape.

The photos he submitted in earning a fellowship were inspired first by the bold colors and textures he noticed on that rusty old Dumpster, then by the natural process of oxidation that Magnani knows created them.

“Other than keeping us alive,” he says, “oxygen spends most of its time destroying almost everything we create. Oxidation, corrosion, rust — call it what you will, it cracks our plastics, peels our paint, ruins our cars, sinks our ships and knocks down our bridges.”

But that process itself, Magnani says, creates a deep beauty worthy of our attention.

His creativity is inspired more by the likes of whatever he can examine exactly where he stands than it is by organized photography expeditions to sites as breathtaking as Yosemite, or the Grand Tetons, or Costa Rica. The costs of such group trips can be prohibitive, he says, and so is the notion of mingling with a gaggle of photographers, each with a tripod perched in the same spot.

Lately, Magnani has been exploring the use of slow shutter speeds to capture different aspects of motion. He’s also grown fond of experimenting with lenses — he finds it easy to adapt old lenses to some new digital cameras. Last year, he took 31 photographs with 31 different lenses. He plans to expand that to 100 lenses.

Masters

Established

Emerging