It’s not uncommon for a person who looks at one of Arden Bardol’s intricate pieces of jewelry art to tell the artist, “Boy, this is just really architectural.” The reason often escapes the viewer, but it makes perfect sense to Bardol.

Her design philosophy was influenced by the way she was taught to think in architecture school. She has practiced architecture for almost 30 years, and she still does so two days a week. She has a love of geometric shapes and of nature, especially flowers.

“In the natural environment,” says Bardol, of Dover, “there is so much geometry and math that is in how things grow. You look at the center of a sunflower — that’s a great example. The way those seed patterns grow from the center of a sunflower is identical in every single flower.”

That’s courtesy of the Fibonacci sequence, as Bardol notes, in which every number after the first two is the sum of the two preceding numbers. It’s a mathematical sequence that appears throughout nature, from pine cones to conch shells.

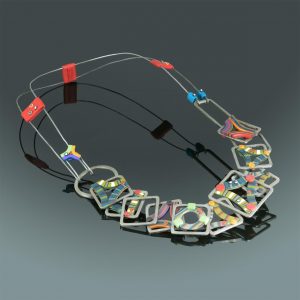

“A lot of my work tends to be a combination of something very structured,” she says, “whether it be a circle or a square, that then has very flowing elements to it that add a softness and a grace. And the combination of those two things is just naturally appealing to people.”

Polymer clay is her medium. It comes pre-colored, and Bardol buys yellow, red, blue, black, white, gold and silver. She has rolling machines that allow her to crank the clay by hand, blending the colors into new hues. To make patterns and textures, she overlays colors, sometimes by stacking paper-thin layers of clay, and then uses a very thin knife to slice through multiple layers. Bardol can make stripes that way, like the cross-section of a cake. She’ll then turn it on its side and roll it flat.

For Bardol, the tactile nature of this work harkens to her youth. Her father was a contractor, and after she was about 8 years old, she would assist him, picking scraps of wallpaper off the floor. She got into weaving and pottery, but by college, a lot of the hands-on practice was eliminated from her life.

Around the age of 50, though, Bardol started playing with polymer clay. It had a consistency and packaging that for her equated to those of porcelain, with which she had worked during her 30s. The medium captured her imagination.

“And I thought, Do I really want to look back and say, ‘What if?’” she says. “‘What if I had followed this polymer/artistic/being-on-my own path rather than continuing in the field of architecture?’ And I didn’t want to have that ‘What if’ moment later in life. If I thought that the artist working on her own was really what I wanted to do, rather than What-if it, give it a try and see what was going to happen. So that’s what I did.”

She needed a project that she could conceive and execute in a reasonable amount of time. Five years, she says, is the time it usually takes her to see a building she’s designed come to fruition. Bardol’s ultimate affection for creating jewelry art wasn’t about instant gratification, but she wanted to birth her ideas more quickly.

She worked with polymer for eight years before she started manipulating steel. The heat that’s required to bond steel, she says, is 10,000 degrees Fahrenheit. The heat that’s required to cure and bond polymer is 300 degrees.

“All of my work is about construction process,” she says. “How do I put this together? And because steel, and all metals, has a completely different coefficient of thermal expansion than polymer does, steel, when it’s heated, expands and contracts at a much greater rate than the polymer does when it’s heated. So if I was to make a steel form, a framework, that I was then going to put the polymer in, my method of connecting the polymer to the steel had to allow for how they expand and contract differently. I knew that I had to suspend the polymer in a steel framework, that I couldn’t physically attach it, because when I put the steel into the kiln with the polymer, even at 290, 300 degrees, the steel was going to move at a faster rate than the polymer was going to move, and so the polymer would crack.

“And that’s very similar to what happens in buildings when you’ve got control joints, which control the expansion and contraction of building materials that move at different rates where they come together.”

She doesn’t believe in giving an object a front or a back side. She treats all sides equally, so that no matter a person’s vantage point, her jewelry will be visually appealing.

Lest a potential customer be concerned about how to enjoy a piece when it isn’t adorning his or her body, Bardol has made a series of shadow boxes that have painterly backdrops of polymer and a clipping mechanism she has devised to hang the jewelry.

This year, as she challenges herself to produce something unique to fulfill her fellowship grant obligations, Bardol is focusing on furthering a dialog between the polymer and steel. She is progressively working with thinner, smaller pieces of metal. She experiments, makes mistakes and practices until she finds the most graceful way to render structurally sound, beautiful welds.

“The smaller you get,” she says. “you could very easily burn a big hole in your project because there isn’t enough area of metal for all of the heat to dissipate.”

Still, the hours fall away. An early morning in her studio seems to quickly become 6 p.m.

“I get into a zen-like place,” Bardol says. “No matter how many mistakes I’ve made during the day, I don’t get frustrated anymore. I take copious notes — I had this much tungsten, and this many amps, and here’s what happened — so that I can get better.”

Masters

Established

Emerging