Upcoming grant deadlines: Applications for 2024 Delaware Writers Retreat and 2025 Individual Artist Fellowships due August 1. More Info

Kids start working on paper from the time they’re little, Ron Meick notes, and in his case, that affinity has stretched a lifetime.

He majored in sculpture at the Rhode Island School of Design, where he would shoot pool with the glass sculptor Dale Chihuly at the Portuguese-American Club. Meick often worked with large pieces of steel. Once out of school, he no longer had access to the materials and tools with which to build such creations.

“Paper,” he says, “is one of those things that’s accessible. I suppose the whole idea of printmaking is something I’ve always liked. Making marks. The first print was the hand in the cave. It’s accessible. And print is certainly more attainable by normal people than a million-dollar painting.

“I say that, but a lot of my things are just one-of-a-kind.”

Meick, 60, started making prints in high school. His current artwork utilizes many techniques of woodworking, metalworking and printing, skills he accumulated through the years.

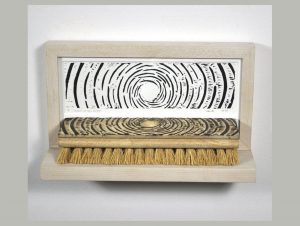

For the Division fellowship, he submitted a series in which he used common singular objects — a hand axe, a wooden crutch, a wooden hanger — to construct relief prints. Each object is presented as part of the print it helped to make, akin to displaying brushes with a painting they were used to render.

Meick, who moved to Arden 10 years ago from New Hampshire and was born in Sidney, Neb., used traditional woodcut and monotype techniques for the mark-making process to reveal, as he puts it, “other implications, ideas, characterizations or personal meanings.” His use of the woodcut, he adds, “links this work to past traditions in a sense like the hand tools or objects link us to a non-digital world that is slowly being lost with the virtual experience.”

His father worked for the government and was stationed in Germany when Meick was in the sixth through 11th grades. Living in Europe exposed him to centuries of the arts.

“That’s kind of where I developed a real passion for the arts,” Meick says. “Things are just much, much older than the things around here. It was important. I was one of those kids who knew exactly what they wanted to do. I just applied to three art schools; nothing was really tugging at me to do something else.”

He happens upon most of the objects that make their way into his work. He got the crutches off eBay. He saw the hanger in a closet and thought it might work. When he knew he wanted a tool used for manual labor, he sought out a scrub brush. His sister-in-law in Texas sent him a sickle.

When it comes down to it, Meick just likes making things, from woodworking to jewelry. (“I figured jewelry was really just a little sculpture,” he says. “If you make it look shiny and it looks like it could probably catch a fish, it’ll probably sell. It’s a lure.”) He plays guitar and some saxophone. (His father started playing sax at 5 years old and, at 86, still plays in two bands in Florida.) He’s also a beekeeper.

Lately, he’s been working on projects that involve the relationship of the matrix (the plate used for printing) and the print. He presents both together to reveal the source and process of the work. Since the year began, Meick has been working on a group of 20 small mezzotints that utilize sound cards.

“Based on the game of 20 questions,” he says, “the questions asked in each soundtrack do not have a specific answer but are basic philosophical or object-specific questions that go outside the boundary of the object. The prints with an image of a crumpled piece of paper are paired with a blank crumpled paper. The paper is attempting to imitate the drawing just as the drawing is trying to define the image of the paper. Ultimately the identity cannot be defined other than what it is or what it is not.”

The Division’s grant will help fund future projects and upgrade the technology Meick uses in his practice.

Masters

Established

Emerging

Fellowship HomeRelated Topics: arts fellowship, arts grants, dance, Delaware, delaware division of the arts, Department of State, Division of the Arts, emerging artist, fellowship, fiction, folk arts, literary arts, literature, media arts, music, performing arts, poetry, recipient, State of Delaware, visual arts