By: Gail Obenreder

“I feel a deep sense of responsibility to contribute to the celebration of black culture and highlight important aspects of daily life, capturing the richness and dignity of represented black bodies.”

Drawing has been a part of Brandan Henry’s life “as far back as I can recall.” As a child, he loved the Great Illustrated Classics book series, and a weekly art class at the Boys and Girls club – led by volunteer artist Joe Russell – “changed my life.” But his journey to becoming an artist didn’t follow a linear path.

Henry has lived most of his life in Wilmington, and “my surroundings and my memories of home, childhood, and family” inspired what he decided to render. Even while he worked at several jobs, “one constant has been my dedication to being aware of the beauty in everyday happenings.” A stint in the Marine Corps gave him a wider world view, and it also provided him with something tangible – the ability to pursue art as a profession.

After four years of military service, Henry “had some education benefits . . . that I needed to utilize.” Though he had not really considered returning to school, he realized that “if I were to do so, it would be for something I was genuinely passionate about – art.” Henry was inspired by the illustrations of Katsuhiro Otomo and the photographs of greats like Gordon Parks, Carrie Mae Weems, and James Van Der Zee, and so enrolling in an art program seemed especially daunting.

It was an exhibition of the artist John Biggers that “expanded my understanding of the potential of art” and gave him the impetus to go forward. Henry was ultimately able to enroll as an art student, first attending the Delaware College of Art and Design as a Fine Arts major and then going on to programs at the University of Delaware, where he received both his BFA and MFA.

Now an accomplished artist with well over a dozen group exhibitions to his credit, he still finds his primary challenge is “attempting to capture the ineffable, and frequently falling short.” Becoming a father, too, has changed him, and he has “used drawing to deepen my understanding of my daughter.”

As well as finding “joy in fatherhood,” Henry is fascinated by architecture as a concept, and he also loves exploring the outer boundaries of experimental music. His interest in travel and diverse cultures, first fostered by his time in the Marines, keeps him “engaged and curious about the world around me.”

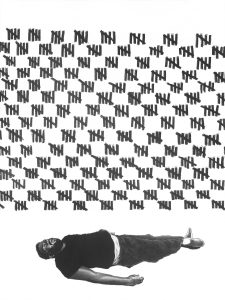

While Henry embraces a “naturalist approach to drawing,” graduate school changed both his artistic practice and his philosophy. Though finding his usual “refuge from misrepresentation in charcoal, chalk, and dust,” there he began to experiment with abstraction, larger drawings, and hints of color. A consistent element in his work is the use of white space, seen in the powerful drawings that earned his Division Fellowship. These artworks “subvert the black/white trope by using the white paper as a void which interrupts and consumes black bodies . . . flipping the idea of invisibility, questioning who becomes unseeable.”

Henry feels “a deep sense of responsibility to contribute to the celebration of black culture . . . capturing the richness and dignity of represented black bodies.” The Division’s award will allow him to deepen his practice by obtaining supplies “that were previously beyond my financial reach,” expanding his artistic network, and taking advantage of “the invaluable opportunity to continue creating the work that I enjoy making.”